By Alastair Bland for NPR.org. Reposted with permission. Full attribution below.

This week, world leaders are hashing out a binding agreement in Paris at the 2015 U.N. Climate Change Conference for curbing greenhouse gas emissions. And for the first time, they’ve made the capture of carbon in soil a formal part of the global response to the climate crisis.

“This is a game changer because soil carbon is now central to how the world manages climate change. I am stunned,” says André Leu, president of IFOAM — Organics International, an organization that promotes organic agriculture and carbon farming worldwide.

Leu is referring to the United Nations Lima-Paris Action Agenda, a sort of side deal aimed at “robust global action towards low carbon and resilient societies.” On Dec. 1, countries, businesses and NGOs signed on to a series of new commitments under the agenda, including several on agriculture.

Currently, the Earth’s atmosphere contains about 400 parts per million of carbon dioxide. Eric Toensmeier, a lecturer at Yale and the author of The Carbon Farming Solution, a book due out in February, says the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide levels must be cut to 350 parts per million or lower to curb climate change.

Toensmeier and Leu are among a growing number of environmental advocates who say one of the best opportunities for drawing carbon back to Earth is for farmers and other land managers to try to sequester more carbon in the soil.

“Reducing emissions is essential, but eventually it still gets us to catastrophic climate change,” says Toensmeier, who’s attending the Paris talks on behalf of the group Project Drawdown. “The level of emissions in the atmosphere now is already past a tipping point. That means we have to sequester carbon.”

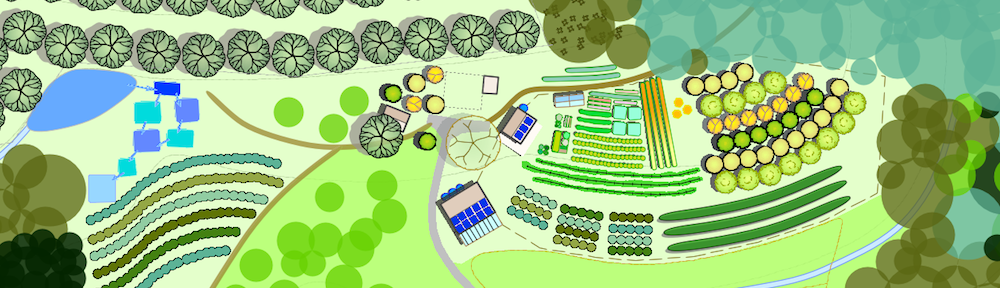

Las Cañadas is an ecological cooperative in Veracruz, Mexico that’s working to sequester carbon and mitigate climate change while producing food, materials, chemicals. Courtesy of Ricardo Romero/Chelsea Green Publishing

Using photosynthesis, plants draw carbon from the air and deposit it in the soil. And farming is a simple way of growing crops and managing soil that, under the right conditions, encourages the buildup of carbon in the ground. In addition to countering global warming, carbon-rich soil can be more productive and hold water better than soil with lower carbon content.

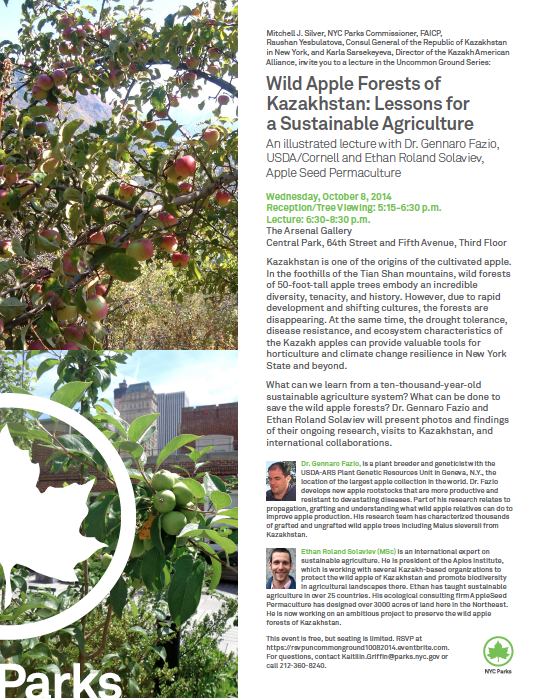

There are two basic ways for farmers to capture it, says Connor Stedman, an agricultural consultant in the Hudson Valley with the firm AppleSeed Permaculture.

“You can put carbon in soil, and you can put carbon in long-lived perennial plants, especially trees,” says Stedman.

And you can start, according to Torri Estrada, managing director with the Carbon Cycle Institute in northern California, by disturbing the land as little as possible.

In conventional industrial agriculture, the soil is often tilled or plowed to disrupt weeds and prepare the land for planting. But turning the soil this way (or overgrazing animals on rangelands) introduces oxygen to the carbon. The carbon and oxygen then can bond into carbon dioxide – a greenhouse gas.

As food production has intensified, between 50 and 80 percent of the soil carbon has been lost around the world, according to researchers at the Ohio State University’s Carbon Management and Sequestration Center.

Gabe Brown grows oats, alfalfa, peas, clover and other field crops in North Dakota. He says that when he bought his land in 1991, his soil’s carbon level registered at a dismal 1.9 percent on average. “It was a tan, lifeless powder,” says Brown, who delivers seminars around the nation on carbon farming and has become a sort of guru of the movement.

But then he decided not to till or plow to boost carbon levels in his soil. And his efforts have paid off. “Now, [the soil] looks like black cottage cheese,” he says, adding that his yields are as much as 25 percent greater than those of conventional farms nearby, and his soil is up to 6 percent carbon on average.

According to Stedman, healthy, undisturbed soil rich in organic matter can contain anywhere from 8 to 20 percent carbon. In addition to minimal tilling and plowing, another way to sequester carbon in soil is to add compost. Cover crops add carbon, too, and also reduce erosion.

But to make a real dent in the carbon dioxide emissions – and climate change — with carbon farming, Stedman says farmers globally would have to deposit on average just over 25 tons of atmospheric carbon into each acre of the Earth’s arable land. That could take decades. And that assumes carbon emissions could also be halted and that all farmers in the world actually participate. Stedman says that, realistically, since only some farmers will be actively trying to sequester carbon in coming decades, it may require depositing much more than 25 tons per acre.

There’s another possible wrinkle in the scheme, says Peter Donovan, a board member of the Soil Carbon Coalition. As carbon is drawn from the atmosphere and into the Earth, the ocean will release some of its own carbon into the air, which could substantially offset the progress of sequestration.

Ecologist Brock Dolman agrees the task at hand is massive.

“Business as usual with conventional agriculture is just contributing to greenhouse gases, soil erosion, ocean dead zones, all of the above,” says Dolman, co-founder of the Occidental Arts and Ecology Center in northern California, which promotes sustainable agriculture. “But to not move forward with carbon farming … well, somebody would have to tell me what else we are going to do.”

There are signs beyond the Lima-Paris Action Agenda, announced in Paris on Dec. 1, that the carbon farming movement is moving forward.

The Carbon Cycle Institute is working with local governments to teach the basics of carbon farming to growers and ranchers around California.

In France, the Ministry of Agriculture, Agrifood and Forestry has launched an international campaign to increase soil carbon content.

There are other ways to sequester carbon besides agriculture and forestry, such as capturing emissions from power plants and piping the carbon to underground storage spaces.

But Estrada says doing so by farming makes the most sense.

“Photosynthesis and soil has been working for billions of years,” he says. “It’s the longest running [research and development] project around, so why not use the simple, well proven one that we know works?”

Alastair Bland is a freelance writer based in San Francisco who covers food, agriculture and the environment.

This article was originally posted on NPR.org. You can find it at:Â http://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2015/12/07/458063708/carbon-farming-gets-a-nod-at-paris-climate-conference

Follow Alastair Bland on Twitter @Allybland

In a Nutshell – A three-month internship with AppleSeed Permaculture, a cutting edge regenerative design firm based in the mid-Hudson River Valley of New York, USA. Internship runs from September 1

In a Nutshell – A three-month internship with AppleSeed Permaculture, a cutting edge regenerative design firm based in the mid-Hudson River Valley of New York, USA. Internship runs from September 1